Reflecting on Listening, Interviews with Global Listeners

Interview of Jo-Ann Rolle, Ph.D.

Vice Chair, Global Listening Board,

Global Listening Centre.

Past President of the National HBCU

Business Deans Roundtable,

Past Dean at School of Business Medgar Ever

College, City University of New York, US.

Interviewer Carin-Isabel Knoop

Chairperson, Global Listening Board,

Global Listening Centre.

Executive Director at Harvard Business School,

Case Research and Writing Group,

Harvard University, US.

Co-Founder of HSIO

Carin-Isabel: How important is listening for business leaders in academic settings?

Dr. Jo-Ann: In universities and colleges, strong listening skills are crucial for business leaders. Effective communication goes beyond just talking. By actively listening to faculty, staff, students, and external partners, leaders can:

- Align strategies with institutional goals: When leaders listen to the needs and concerns of their stakeholders, they can develop strategic plans that truly reflect the institution’s mission and vision.

- Foster collaboration and respect: Active listening creates a space where everyone feels heard and valued. This fosters a more collaborative and respectful environment, leading to better problem-solving and innovation.

- Improve decision-making: Leaders who consider all viewpoints can make more informed decisions. Listening ensures a well-rounded understanding of any situation before a course of action is chosen.

Carin-Isabel: How can young business leaders develop their skills?

Dr. Jo-Ann: Young leaders can hone their management and leadership skills through:

- Academic programs: Many universities offer courses and programs specifically designed to develop leadership skills.

- Leadership roles in student organizations: Participating in student government or clubs provides valuable experience in leading teams, managing projects, and navigating group dynamics.

- Mentorship: Engaging with experienced faculty mentors can offer guidance and support as young leaders develop their skills.

- Committee participation: Serving on administrative committees allows them to observe decision -making processes firsthand and contribute their own ideas.

Crucially, listening skills training is an essential part of this development. Leaders should learn active listening techniques like summarizing key points, asking clarifying questions, and showing genuine interest in what others have to say.

Carin-Isabel: How does Artificial Intelligence (AI) impact business management in academia?

Dr. Jo-Ann: Artificial Intelligence (AI) has a noticeable effect on business management in academic settings. AI can analyze vast amounts of data to provide insights on areas like:

- Student performance: AI can identify at-risk students and recommend interventions to improve their success.

- Resource allocation: AI can analyze data on course enrollment and faculty workload to ensure resources are distributed efficiently.

- Personalized learning: AI can develop customized learning pathways for each student, catering to different learning styles and needs.

Listening to AI outputs is becoming an important skill for business leaders. By critically analyzing AI recommendations, leaders can leverage this technology to improve educational practices, streamline administrative operations, and ultimately benefit students, faculty, and staff alike. However, it’s crucial to ensure AI serves the institution’s mission effectively, not replace human judgment and understanding.

Dr. Jo-Ann: Based on your own experience and research, how important would you say, effective listening is in achieving and maintaining one’s mental health and personal stability?

Carin-Isabel: Let me start with a definition because it is essential to agree on terms here. According to the World Health Organization, mental health is the ability to deal with normal stressors of life and work and contribute to your community to the extent desired. To me, this is impossible without being able to be listened to (that includes listening to ourselves and others). Without being able to be listened to it is hard to make connections. Without the ability to connect, we lose our ability to operate as a compassionate person who can show concern for the misfortunes or suffering of other people—but also for our own. Only thus can we be sympathetic to the situation. So, I believe there really cannot be any compassion without listening and paying attention—to understand the situation. This is the first and fundamental part.

The second is respect. Nodding distractedly while someone expresses anguish is not compassion—it is dishonest and erodes trust. It is then better to politely ask to postpone a conversation unless it is urgent.

Third, I would say honesty and vulnerability – showing compassion requires my being comfortable expressing how the situation might make me feel. It might be having what a 2016 book called Emotional Agility (by Susan David). This implies a leader who can recognize her thoughts and feelings and be flexible with them so that she can “show up,” as Americans say. But this means that she will also treat herself with compassion and not dwell on mistakes—which is essential for leaders— especially in our period of rapid digital change, but also rapid social change, high performance and reputational risk.

Dr. Jo-Ann: Has the evolution of Artificial Intelligence contributed to or detracted from overall mental health maintenance?

Carin-Isabel: The pandemic upset the balance of power in many workplaces and inflicted significant psychological damage on many generations. Some employees demand more flexibility and seem less willing to trade off their health and well-being for classic measures of organizational success. The pandemic and working at home also dramatically increased our use of technology for information, discord, and comfort. This seems to have been ever more the case with children who were kept at home and schooled online.

There is an unpopular saying by former President Ronald Reagan in the US—Guns don’t kill people, people kill people. We are blaming social media for additional and depression problems, but those might have been the very reason why people turned to phones and technology. One of the most popular apps on OpenAI is “AI Girlfriend”—which fills a loneliness gap. People are also “recreating” lost ones and using mental health apps with little grounding in science.

On the bright side, GenAI can get our work done faster, lowering our stress and helping us apply to better jobs or companies that will pay fairly and support better work conditions.

And GenAI can be a good companion—always there, always kind, always patient. It does not sleep or have a bad day. We are blurring lines with affective technology. It is too early to understand its impacts, in my opinion.

Dr. Jo-Ann: What would you say are today’s major challenges when it comes to effective listening and mental health maintenance?

Carin-Isabel: With empathy usually comes emotion. With compassion, there is emotion but also action or an expectation of action.

So being empathetic is about putting ourselves in a position that allows us to feel what others might feel in a situation; compassion, of course, also requires emotion, but it is also associated with the desire to do something about it. When I am feeling unwell or struggling with anxiety and depression, this becomes more difficult. I might be more impatient or judgemental.

Talking to leaders but also anyone who can understand and share our feelings can be very powerful – it enables us to feel understood and cared for even if nothing concrete happens. The connection and reassurance that we are seen and heard is the reward. Taking another person’s perspective can be very challenging, so it can create strong bonds when people do it genuinely.

When we don’t our mental health usually suffers – perhaps not immediately but the corrosion will occur progressively until suddenly we break.

Compassionate leaders and managers listen enough to know when they are moving too much, too hard, or too fast. Because they understand they also know how much to challenge in a productive way to make the best use of the company’s resources and the opportunities it can seize. And because they are honest, they present as post-heroic—and make people feel more at ease with sharing mental health struggles.

Interview of Professor Patricia M. Davidson,

Ph.D., MEd, RN, FAAN

Rated one among the Top 25 Outstanding Women

Listener in the World 2021,

Global Listening Centre.

Vice-Chancellor and President at

University of Wollongong, Australia.

Interviewer Professor Grace McCarthy,

Ph.D., MBA

Director, Global Listening Centre.

Dean at Sydney Business School, University of

Wollongong, Australia

Prof. McCarthy: Thank you for making time today to talk about listening. You were named as one of the Outstanding Women Listeners in the World in 2021. At what point in your life or career did you realize the significance of active listening for your personal and professional success?

Prof. Davidson: I actually had a bit of an epiphany in 2003 when I was using motivational interviewing for behavioral change in heart disease. As part of the training, they measure the proportion of time you speak and the proportion of time the patient or subject speaks. As nurses, we are trained to tell people what to do. Since that time, I have been really aware of the value of listening.

Prof. McCarthy: What sets your approach to listening apart in your leadership roles, both during your tenure as the Dean at Johns Hopkins and now as Vice-Chancellor at the University of Wollongong in Australia?

Prof. Davidson: We’ve all made transitions in our careers, but we can’t negate our original professional training. I’m an intensive care nurse. I’m trained to solve problems. When people come to me, I instinctively think about solutions – I have had to slow that process down consciously, to be more patient and really listen to other people and hear their ideas.

Prof. McCarthy: How have your listening skills evolved, and what impact has this evolution had on your leadership style and the outcomes of your initiatives?

Prof. Davidson: The higher up you go, the more ambiguity and uncertainty there is. When we have a complex problem, I bring people together and say there is no right or wrong, but we have multiple perspectives in the room. We have to think not only about what is legal but also what is right. I articulate my own biases so that people know where I’m coming from. And I explain that when we take a collective decision, it is the best decision we can make at that time, and I tell them that I will back them when we implement that decision.

Effective listening is part of having courageous conversations – you have to be prepared to listen and be prepared to change your point of view. Challenging conversations should not be seen as criticism. There is a lot of focus now on risk. Listening helps us to identify a broader range of risks. It is important for leaders to be accessible. When people come to see me with a complaint, I listen and then send them where they need to be. If I didn’t listen to them, the problem would escalate and possibly be vented outside the organization, with the media, social media or courts. A lot of problems can be resolved at a lower level when people feel heard. Listening helps us get at the root cause of problems, rather than simply throw money at the symptoms. If Outstanding Listeners Interview A conversation with Patricia M. Davidson by Grace McCarthy Professor Patricia M. Davidson, Ph.D., MEd, RN, FAAN Rated one among the Top 25 Outstanding Women Listener in the World 2021, Global Listening Centre. Vice-Chancellor and President at University of Wollongong, Australia. Professor Grace McCarthy, Ph.D., MBA Director, Global Listening Centre. Dean at Sydney Business School, University of Wollongong, Australia The Global Listener DECEMBER 2023, ISSUE 9 2 1 someone complains, money may make them go away for a time but doesn’t solve any underlying issues.

Prof. McCarthy: The term “listening environment” has been used to describe an organizational culture where listening is valued. What can a leader do to establish listening as a key component of the organization’s culture?

Prof. Davidson: The radical thing I would do is burn organization charts. Everyone should be valued, no matter who they are or what they do or what level they are at. Role modeling is important, not just by me but by all our executives. We need to value listening across the organization, perhaps even give a listening award. In terms of communication, I think more frequent and smaller meetings with staff may help people feel heard and appreciated.

Listening should not be seen as something soft and fuzzy, but rather as something we do as part of being accountable and taking responsibility for living the organization’s values. In a large, complex and diverse organization, we have to be thoughtful and intentional about our culture and values.

Prof. McCarthy: Your work has significantly contributed to healthcare and nursing research. How has active listening shaped your research endeavors?

Prof. Davidson: Qualitative research used to be seen as soft and fluffy. Now, qualitative research is valued in nursing and across healthcare. The notion of listening has really changed how we do research. We now listen to patients. We co-design and cocreate research with participants and develop interventions that are appropriate for the target group. We listen to understand why an intervention has or has not been effective.

Prof. McCarthy: If you could apply your thoughts on the importance of listening to the global arena, what is the parting message you would like to convey? Prof. Davidson: We have to have humility, acknowledge our own frailties, and be willing to show vulnerability. In these tumultuous times with conflict in many parts of the globe, it is more important than ever to listen to each other and connect with each other as human beings. We also need the courage to stand up for human rights and speak up for what is right. Listening helps us understand the perspectives of others and that can form the basis for peace.

Interview of Hon. Juliana Yvonne O’Connor-Connolly, LLB., B.A.

(Honours/Summa Cumma Laude) MP, JP

Deputy Premier & Minister for Education, District Administration & Lands, Cayman Islands.

Interviewer David T. McMahan, Ph.D., Executive Chair of the Global Listening Centre & Mr. Sardool Singh, Chief Global Strategist of the Global Listening Centre.

Sardool: In the context of the Caribbean Region, how important is listening to regional development?

Juliana: Effective regional development in the Caribbean requires inclusive decision-making processes that consider all stakeholders, including Governments, Communities and Civil Society Organizations, diverse perspectives, needs, and aspirations. It is essential to listen attentively to the voices of all the citizens and stakeholders to identify key issues and challenges affecting the region’s development. Regional policymakers can then prioritize and allocate the limited resources effectively by understanding these issues and engaging in open dialogue, consultations, public engagement and reciprocal accountability.

David: How has the art of listening impacted your career as a legislator in the Cayman Islands?

Juliana: My ability to listen has facilitated the following:

- Constituent Engagement: As a legislator, my main priority is to represent the interests and concerns of my constituents. By actively listening to them and taking their needs, opinions, and feedback seriously, I am more cognizant of their various and diverse issues. This allows me to make informed decisions and craft legislation that aligns with their interests.

- Relationship Building: Listening attentively to constituents and other stakeholders has also helped me build strong and treasured relationships. I have found that people are more likely to trust and support me when they feel heard and understood. This has also led to collaborations and partnerships that have been critical to my work as a legislator.

- Identifying Issues and Solutions: Effective listening has enabled me to identify emerging issues and potential solutions. I can discern patterns and areas requiring legislative attention by paying close attention to conversations, public opinion, and feedback from various other sources.

- Conflict Resolution: Conflict Resolution: In the Westminster styled Parliamentarian legislative process, conflicts and disagreements are common. However, my ability to listen to the various perspectives and my ability to negotiate until common ground is attained, has allowed me to resolve several disputes, especially during my tenure as House Speaker.

David: Can you offer any suggestions for more effective listening amongst parliamentarians?

Juliana: As Parliamentarians, especially those who are newly elected, we must cultivate strong listening skills. One effective way to achieve this is by attending training sessions and workshops emphasizing active listening techniques. This will allow us to foster better communication and promote a greater understanding among our fellow legislators.

I also encourage fellow Parliamentarians to embrace various technology platforms such as social media, online surveys, and interactive websites to further hone our ability to listen effectively to the public. These tools will enable us to gauge public opinion on specific issues or proposed legislation. Regular engagement with our constituents is crucial. Through town hall meetings, public forums, and individual meetings, we can actively listen to their concerns, ideas, and feedback on legislation. By engaging directly with our constituents, we can better comprehend their needs and represent them more effectively in the legislative process. It is also essential to reflect on the feedback and suggestions we receive. By actively considering different viewpoints and weighing them against our own beliefs and values, we can refine our legislative approach and make more informed decisions based on the needs and desires of those we serve.

David: In education, listening is a simple but vital and effective tool. In your opinion, to what extent is it effectively used by our educators?

Juliana: Effective listening is a crucial skill for educators, but it can vary depending on their teaching style, experience, and level of professional development. Here are a few factors that we should consider when determining how well educators listen:

- Active Listening: Successful educators practice active listening by giving their full attention to students, understanding their perspectives, and responding appropriately. This involves being present, maintaining eye contact, and showing a genuine interest in what students have to say. By actively listening, educators create a supportive environment that fosters engagement and participation. Simply put a classroom must provide a student-centered environment.

- Feedback and Assessment: Careful listening is essential for providing feedback and assessment to students. Educators who listen closely to student responses, questions, and concerns can give timely and constructive feedback that supports academic growth. By understanding students’ knowledge gaps, misconceptions, and learning styles, educators can provide targeted support that helps students succeed.

- Classroom Management: Listening is also crucial Outstanding Listener‘s Interview The Global Listener JUNE 2023, ISSUE 8 1 9 Listening Transforms Lives for effective classroom management. Educators who listen to their students can anticipate and address potential issues before they escalate. Educators can respond appropriately, diffuse conflicts, and maintain a positive and inclusive learning environment by being aware of students’ nonverbal cues, tone of voice, and emotions.

- Building Relationships: Listening is a fundamental element in building positive teacher-student relationships. When educators actively listen to students, they show empathy, respect, and understanding. This helps foster trust, rapport, and a sense of belonging, which is essential for student engagement, motivation, and overall well-being.

- Parent-Teacher Communication: Effective educators also utilize listening skills when engaging with parents or guardians as they can establish strong partnerships and work collaboratively to support student success by listening to families’ concerns, goals, and opinions

David: Do you change your listening style in different situations? Is listening different in the legal field? Or in private life?

Juliana: Adjusting my listening approach to suit each specific scenario has proven effective, whether practicing law, participating in parliamentary proceedings, or engaging in personal conversations. It requires more than merely listening in the traditional sense, but rather utilizing each of our five senses to meticulously receive, coalate, and analyze what is being said or done albeit verbally, expressly or subliminally. Nevertheless, regardless of context, I always aim to integrate empathetic, analytical, and solution-focused listening strategies. Rendering one’s undivided attention to the circumstances and or communicator is not always easy, but it is essential in the art of listening.

Sardool: What would you say are the most important characteristics of a good listener?

Juliana: To become a good listener, one must embody several crucial qualities, such as attentiveness, empathy, patience, active engagement, and a keen memory for follow-up. To foster trust and mutual respect, it is imperative to display a sincere interest in the speaker’s words, maintain eye contact, and avoid any potential distractions. In addition, striving to comprehend and appreciate the speaker’s experiences and viewpoints, responding with kindness, and providing ample time for expression can cultivate a secure and encouraging atmosphere. By actively participating in the conversation through thoughtful inquiries and thoughtful contributions, one can also facilitate a more meaningful exchange of ideas. Lastly, cherishing the speaker’s contributions by recalling pertinent details and following up on any actionable items can reinforce and strengthen relationships.

Sardool: In your experience, have you noticed changes in how men listen to women who hold important positions? In other words, are men more respectful of women’s perspectives now than they were in past decades? If so, what do you think has caused this change?

Juliana: Throughout my years in politics, I have observed a notable shift towards recognising and valuing the contributions and perspectives of women. This positive development may be attributed to the growing awareness of gender equality and the significance of women’s viewpoints, particularly in professional settings. One recent statistic revealed that women currently occupy approximately 44% of leadership positions in both public and private sectors, here in the Cayman Islands, a heartening reality that may have also challenged gender stereotypes and prompted our male colleagues to reevaluate their assumptions and appreciate our insights more fully. At the end of the day, our respective communities consist of both male and female and in a representative democracy, more can be achieved working in collaboration together.

Interview of Andrew D. Wolvin, Ph.D., Honorable Director (Academic) Global Listening Centre. Professor Emeritus at University of Maryland, Adjunct Professor at the Georgetown University, Law Center. USA.

Interviewer Alan R. Ehrlich, Chair and Director (Listening Disorders), Global Listening Centre.

Alan : You were a major author in the listening field.What change have you seen over your career? And what do you think this has meant for the field?

Andrew : The study of listening as a sub-field of the communication discipline evolved slowly. Some of the first serious research came about in the early 1970s when Larry Barker published Listening Behavior and Carl Weaver published Human Listening, detailed scholarly looks at the complexities of the process. In 1979, Carolyn Coakley and I published Listening Instruction, a National Communication Association publication which provided a theory/research basis for effective teaching and development of listening skills. In 1980, a group of listening scholars and educators came together to form the International Listening Association, providing an organization for people who were researching and teaching listening in schools and colleges. These efforts certainly formed the basis for building the research, teaching and practice in which we engage today.

Alan : Are there any new developments in the field that you think show promise?

Andrew : The current focus on listening is very much centered on listening in second language education and practice and on listening leadership in organizations. This provides us with a broader application of the principles and practices of listening.

Alan : More specifically, how do you feel about listen[1]ing in politics in the US? Do you have any insight about how we could help people to listen better politically?

Andrew : Today’s U.S. political scene is a serious case study of what those of us who teach and research listening stress—be willing to listen to other points of view. It is alarming to observe how much we seem to have lost this perspective.

Alan : How do you find listening/communication relevant in our everyday life that includes communication technology such as social media?

Andrew : A major challenge we face today is the pervasiveness of social media. We’re tied to our iPhones and, consequently, miss a great deal in life— engaging conversations with others, experiences in nature, enjoying different artistic forms, etc.

Alan : Any thoughts about global listening, or listening in general, you want to share?

Andrew : My colleague Annie Rappeport (who just completed her Ph.D. in Peace Studies at the University of Maryland) and I are looking at various dimensions of global listening in our research studies. Listening to each other is certainly central to resolving global conflicts and achieving world peace. Indeed, I’ve been working on a book on the role of listening in foreign policy—how much diplomacy, defense, and development efforts to accomplishing world order.

Alan : There have always been barriers to effective listening but it seems that in today’s world the barriers are becoming more difficult to breach. Is there a method that you teach to help your students overcome their personal barriers and cognitive biases and empower them to be better listeners?

Andrew : I’ve always stressed in my academic courses and in my extensive training and development professional seminars that the barriers to effective listening requires three dimensions: motivation to be a willing listener; cognitive understanding of what the complex process of listening involves, and applying listening skills to be an effective listener,

Alan : The University has always been a melting pot of languages and cultures. Effective listening can be a challenge, especially to those with any level of hearing loss, when the listener encounters a strong ‘foreign’ accent. Is there a technique that you recommend to help students who have a professor with a strong accent?

Andrew : One of the challenges listeners have in today’s global village is to understand another person’s cultural perspective and his/her verbal and nonverbal language. This has been complicated by the covid crisis masking requirement. Listening has so traditionally been inter[1]changed with hearing. However, we listen with all of our senses,

Alan : Can effective listening help a listener separate facts from misinformation or disinformation

Andrew : Indeed, one of the principles that Ralph Nichols, an influential pioneer in listening behavior, stressed the importance of separating facts and principles. As we’ve noted, listeners must be willing to listen to and understand another person’s point of view in order to make a decision to accept or reject it.

Alan : Are we getting any closer to a Unified Definition of Listening?

Andrew : I’m not sure we will ever come to agreement as to what really constitutes “listening.” I’ve always stressed to students to not use the expression “just listen” or “simply listen.” Listening is one of the most complex of all human behaviors, and we need to start with that understanding. (ready to prove)

Alan : Advances in technology have moved personal communication from one-to-one (a two-way conversation), to one-to-many collocated (large groups, rallies, speeches), to one-to-many globally dispersed (radio, television, internet, social media). How has this changed the quality of our listening (memory, biases, comprehension, need for prior subject knowledge)?

Andrew : Technology today has enabled us to connect across that world, making it possible for organizations to bring people together for meetings, training, enter[1]tainment, etc. This direct connection, however, requires that we engage fully. And that focus is difficult in that the human attention span is shrinking considerably. Speakers today in one-on-one, group, or audience settings need to adapt to that reality.

Alan : You have been a leader in listening education and research for many years. How has the study of and teaching of listening changed over these years? What are the greatest needs in listening education and listen[1]ing research for the future? What are your thoughts on a global program for listening education that begins in pre -school and early education venues?

Andrew : I’ve been fortunate to have had wonderful graduate students who have been my colleagues in my work on listening behavior. As those of us who have taught courses and units in listening at all levels of education have retired, I think the focus on listening in the academic world has shifted significantly to second language listening. While this connects us globally, I am concerned as to where we are left in the communication field. Communication departments are focused on messages and messengers in rhetorical, public relations, and communication science studies. Today, it’s more important than ever to turn out students who are listeners.

Meanwhile, it’s encouraging that organizations are embracing the need to establish a listening culture to be responsive to the needs of customers and employees through listening leadership. And it’s wonderful that the Global Listening Centre is providing a significant foundation for that leadership throughout the world.

Interview of Snjezana Prijic–Samarzija, Ph.D. Professor & Rector at The University of Rijeka, Croatia.

Interviewer Professor Jasmina Havranek, Ph.D. Senior Vice President (Academic Affairs) Global Listening Centre. Former Director: Croatian Agency for Science and Higher Education.

Jasmina: As a head of a university and philosopher, who has championed the importance of listening, can you share how you have evolved as a listener? What do you do differently today than, perhaps, ten years ago?

Snježana: I came to comprehend the significance of listening with experience. I wasn’t originally a listener: as a young, underrepresented female scientist, I thought that the objective of deliberation and philosophical discussion was to express your perspective, make persuasive arguments, and convince others that your viewpoint was correct. I reduced listening to hearing what others thought and stood for. My outlook genuinely caught my attention, endeavouring to grasp what I believed about the dialogue’s topic. With time, I recognized that was how other people also perceived conversations, including my colleagues at the university. And while it’s an approach and a concept moderately appropriate for scientific debates, it has proven questionable at the position of university management, where I must make decisions, coordinate with others, and find the best possible solutions.

I realized that the communicatory strategy where everyone is focused on their stance and arguments they could mobilize for their purposes, as sophisticated as it might be, closes us to others. Such inaccessibility hinders from stepping in someone else’s shoes and observing the broader picture. In some cases, it even exhibits a lack of care and makes conflict resolution more difficult. Listening, giving others time to share their thoughts, and maintaining an honest desire to understand someone else’s position, context, and motivation through conversing with them has proven to be a better strategy than merely explaining my position. Listening isn’t just an act of perception: it’s an intellectual and ethical attitude that demonstrates our desire to understand others, appreciate their motives and arguments, and seek either conflict resolution or rational disagreement. In a world that abounds in challenges, I am increasingly convinced we need more listening and inclusivity.

Jasmina: Can you discuss how your leadership has been influenced by your listening? And can you address how problems could be better addressed if people were better listeners?

Snježana: The listener’s attitude in everyday work is that you genuinely seek to understand and appreciate another person’s stance. At first glance, I often disagree with other people’s requirements at my job because it seems as if they want to impose their individual perspective regardless of the fact it isn’t optimal for the institution. They strike me as eager to levy their interests or demand a privileged position. Listening is an attitude that enables me to subdue this starting resistance, suppress it, and attempt to understand why someone may believe they have earned a privileged position. Sometimes it comes to light that it is not an appeal for unfair conduct but a plea to remedy a past wrong, usually a form of discrimination. Sometimes, they believe they have demonstrated superior results that would justify such exceptional treatment. Sometimes there are cases where a person fears letting down those who compelled them to vouch for them, and sometimes they fear taking on new responsibilities. I have found a different solution or a different form of compromise in all these cases. Listening enables gradual harmonization and the skill of calibrating different positions that leads to valuable long-term solutions.

Jasmina: Listening can be a very complex process. Can you talk about tools or skills that are important for listening?

Snježana: You’re correct. It’s a complex process as it involves epistemic and ethical stances and the skill of moderating a conversation. It is natural for each person to feel resistance towards a different opinion that makes demands of our behavior. We call that cognitive dissonance. The farther away the other person’s attitude is from ours, the more pronounced dissonance we feel. As if it was an automatic process, we immediately amass counterarguments. Listening requires us to understand the possibility of a rationally grounded dissonance and how vital it is to control our reactions.

It requires the ethical attitude of respecting another person and the epistemic philosophy of exploring a topic in depth from another perspective before disqualifying someone or offering undue criticism. Listening is also the skill of leading quality conversations and the ability to ask constructive and benevolent questions rather than overarching, nosy, disdainful, or arrogant inquiries.

Jasmina: Do you have a philosophical position on listening?

Snježana: In philosophy, I endorse virtue epistemology, a position that focuses on the knower’s – or epistemic agent’s – intellectual virtues. For me, listening is a kind of intellectual virtue that includes intellectual curiosity, humility, conscientiousness, and responsibility. Listening presupposes a curious yet humble attitude, a desire to learn, and the consciousness that we don’t always know everything that we have maybe failed to assess the question from a perspective we still cannot see, that there is always the possibility we have made a mistake, and we can improve our belief. That’s precisely why, for me, listening is an act of epistemic conscientiousness and responsible conduct towards knowledge. Listening is undoubtedly a potent tool if we hope to approach correct attitudes or the truth.

Jasmina: What role does “ethics” play in listening, and from an ethical standpoint, what difference can ethical listening make in an organization’s …or a government’s… plans and programs?

Snježana: Listening encompasses the ethical attitude of respecting others, difference, diversity, plurality, difference, diversity, plurality, and inclusiveness. All of these are vital elements comprising the idea of academic integrity. Universities must be locations to rethink and practice ethical behavior and areas whose example should lead the political and broader community for- ward. I believe that we at universities have plenty more room to grow in that sense, to educate students and oth- er citizens. Listening is a building block of the trust we are trying to achieve in citizens and the community.

Jasmina: In the context of higher education, does social media provide you with a listening tool?

Snježana: Social media is our reality. It has brought a lot of good, by which I’m speaking primarily of democratizing information-sharing and communication. Today all information is accessible to everyone and can no longer be the space of manipulation and powerplay. However, social media have burdened us with many challenges, so today, we all live in our informational bubbles where we exchange opinions with like-minded peers. Search algorithms present us with sources that confirm what we already think. It leads to us becoming all the surer of our stances and even more critical of others. Moreover, it leads to extremization as some informational bubbles function as echo chambers. People in them don’t only not listen to people who hold different opinions, but they refuse to hear them and perceive them as threats. I think it’s an occurrence that we must become aware of as soon as possible as it is the exact opposite of all the ethical and intellectual virtues that comprise listening.

Interview of Dr. Donde Plowman, Chancellor of the University of Tennessee at Knoxville.

Interviewer Dr. Sally J. McMillan, Director (Global Strategy & Corporate Listening) Global Listening Centre, Professor of Advertising and Public Relations at the University of Tennessee at Knoxville.

McMillan: Thank you for talking with us about listening. Please share with us why listening is important to you.

Plowman: It’s so basic because without knowing what people are thinking about and what is on their hearts and minds leaders don’t know what to do. These jobs are way too complex for the leader to really know what the path forward is on so many different dimensions. If you think about higher education right now, it just feels like we’ve got a complex path. Public universities have to secure our funding every year. We have an unclear path about how we’re going to re-envision ourselves to be more modern and more driven around customer needs. When I first took this job, I spent a semester doing a listening tour. I started holding office hours. And I was surprised at how much it helped me quickly get a sense of what the campus pulse was. I was trying to listen, through the structure as well, but also setting up opportunities to listen outside the structure. It was a little unnerving. At times I would hear things in office hours that I wouldn’t have known about otherwise, and then I would call a dean and say, “Some kids came over today, and they were upset about a professor.” I told him it’s up to the dean to address college business, but I just wanted to let him know what I’d heard. I’d also hear from the faculty and staff. It was really helpful to me. I could quickly learn about what people were worried about happy about, and so on. I think listening is crucial.

McMillan: Let’s transition to the topic of social media and social media listening. In the context of advertising and marketing, social media listening is becoming a very important strategy. In the context of higher education, does social media provide you with a listening tool?

Plowman: It provides a way to listen to “noise.” What you do with that noise is something else. Unfortunately, I think social media is used just to talk—or scream. Last fall we were in midst of having to make some big changes in football, including the head football coach and others in the football program, and an NCAA investigation. There’s a very active group of alumni on Twitter who really wanted an answer from me about what we were doing. Why are you doing this? Don’t do this, do this. And in those early weeks I couldn’t respond to anything—and I still can’t talk about that investigation. My not speaking back on Twitter infuriated some of those alumni. There is an expectation out there that that people are listening on social media and quickly responding. I asked my team to get me some social media listening metrics because it felt like I was just getting overwhelmed with pressure from social media. But it turned out it was only about 30 different people who were originating all those messages. Five or six of them were the most vocal. I have 10,000 followers on Twitter. It’s hard to discern what they all are thinking. So listening is hard. I think you end up in an echo chamber on social media and you have to remember that. You have to be really careful about what it is you’re hearing, you know. Social media complicates everything. I still use it, even though there’s a lot of risk with that. I use it to share the brand of UT, share the values of UT, share what we’re trying to build, share the spirit of what this place is. I use it more for speaking than listening. I do listen through it, but I’m not sure what I’m hearing a lot of time.

McMillan: Do you personally read your Twitter feed?

Plowman: Yes. I do read it personally. Sometimes my team will say, “Don’t read it, it’s not nice.” I think it is reflecting everything else that has been going on in society. Vitriol. Divisiveness. Every now and then I’ll look up a particularly nasty comment. It’s not always the case, but many times posters don’t even use their own names. One had only a single follower. It tells me something. I don’t like how people use social media to say such ugly things that they would never say to a person’s face.

McMillan: Social media listening tools can also help with picking up on some of those less-dominant things—help you hear a bit more nuance of what people are saying in social media.

Plowman: Yes, the engagement metrics are very interesting. Since COVID-19, we have been doing virtual alumni tailgates. And out of that came over a million engagements. Social media is not just about shouting. But it does require us to learn new ways of listening and gauging what’s really important. I’m hungry for that kind of data. Another way that I use social media to listen, is, I follow a lot of people—thought leaders in higher education, presidents, and so on. That form of listening helps me to know what others are thinking about solving the big problems that higher education faces.

McMillan: You’ve touched on the idea of social media as a tool for speaking rather than listening. Could you expand on that a bit? Do you see that to be the case in higher education?

Plowman: Oh, yes. I was just reading something about a president who was fired at another university. Part of the pressure around firing him was created just because of news that gets out so quickly on social media. And I think some of it is dangerous because it sets an expectation for immediate response to things. If you didn’t take the action that the people who are tweeting want, then it looks like you haven’t responded. You may have taken an action. But you may just have a different vision about what is the right action. And then sometimes it’s tricky to know how much to put out there. In some ways it sounds like a crybaby, but these jobs are getting harder and harder because of social media, and there is this kind of mob mentality that takes over. All of a sudden, it can feel like there’s a crisis. I just don’t ever want to be making decisions where it feels like I just gave in to a mob on social media. I know some higher education leaders are just leaving social media. I understand the desire to do that. Social media can influence your judgment. But that doesn’t feel like the right answer. Just because you aren’t reading it doesn’t keep the fury from developing. And a part of the community can be very upset. They’re still upset, but if you weren’t on social media, you wouldn’t know it. It would still be true. And it does bleed over, and I mean you’re going to find out.

McMillan: Yes, there are multiple examples of social media elevating something that is a concern for a small group of people and making people believe that it is a “crisis.”

Plowman: Everything’s politicized now, everything. And everything can become a weapon that just further divides us. Pick a topic and it can become a weapon even if it affects a tiny percent of the population – everyone has an opinion. And opinions are often used to divide us. As a leader I am charged with the well-being of all students, faculty, staff, yet often there are conflicting needs and opinions. How does a leader decide what to pay attention to, what to act on? If one person is suffering, that’s not a good thing. What is the leader’s responsibility around one person? Or let’s consider the one student who feels that in a classroom they were stereotyped or marginalized. That is significant to that student, as it would be to me. And it’s significant to the institution, yet at the same time, the leaders have to weigh what that means in the total context of dealing systematically with issues like discrimination and marginalization. These are hot button topics.

McMillan: You have talked about how you did a “listening tour” and how you use social media for listening. Could you talk a bit more about other tools you use for listening?

Plowman: I just got off a call with the deans and the cabinet. Listening carefully to the members of my team is critical. It includes looking at people’s body language and eliciting responses from people. I start every cabinet meeting with an agenda item for reflection. I start with a question. It may be something as simple as, “What accomplishments to you feel best about this week?” or, “What went wrong last week that this group can help you with?” or, “What great thing happened over the weekend in your family?” I like to get the group warmed up and move to a slightly more personal level where people might be slightly more prone to talk and speak up. It’s hard on Zoom, but it’s important for building a culture of shared leadership. We are all in this together. Also, when I do performance evaluations, I ask my team members, “What do you need from me this coming year?” I try to end most meetings by asking, “What do you need for me to be able to do what you just talked about?” Leaders need to ask questions and listen carefully to the answers. I guess in the old days we call that active listening, right?

McMillan: Right!

Plowman: I think as a leader, sometimes you do things that really have a functional outcome; there are other things you do that are more symbolic. Ever since I was a dean, I’ve always held office hours. The truth is, over the years, a very low percentage of students or faculty use the office hours, but they love the idea that it’s there. It’s like sending a message that I’m here to listen. I’m inviting them to walk in and tell me whatever they would like. I’m not necessarily going to give the answer they want, but they like to know that they have a leader who is willing to listen.

McMillan: The willingness to listen is a powerful message in itself.

Plowman: When I first started office hours here, there would be a long line of people waiting to see me. And then, with time, the demand for it decreased. Then with COVID-19 what we found was they did come to Zoom office hours. And then, once we came back to campus, I decided to do office hours part-time here on campus and part-time on Zoom. But no one came to the on-campus hours at all. The technology for meeting and listening is changing. We have to make sure we are meeting people’s needs with tools they are comfortable using.

McMillan: How could higher education play a role in improving listening in contemporary society?

Plowman: I think we need to teach our students how to listen. They need to understand that dialogue is not just shouting on social media. They need to learn to disagree and civilly listen to different points of view. They need to understand that disagreement doesn’t mean that the other person is evil or something. Shouting on social media feels like there is no opportunity to really talk. We need to teach students how to have respectful, meaningful dialogue. I feel like in the first year, we need to get students in a course and talk about civil discourse, freedom of speech, and respect. Because if we don’t teach them those things, they’re going to leave here and become people who scream at each other. We can’t solve all the problems in our society, but higher education has a platform. We need to start reflecting on what’s going on in society and provide an opportunity for personal growth. We need to insist on respectful interaction and open dialogue on campus. We need to stop dividing people into “camps” – faculty vs. administrators, students vs. staff, etc. We need to model that behavior. Our students can begin to change the world. I don’t know all the answers for how to do that. But I am committed to do working to make it happen.

McMillan: I look forward to seeing what you do.

Our Ethics Committee Chair Kirk Hazlett interviewed Craig Newmark, founder of Craigslist and Craig Newmark Philanthropies.

Kirk: For starters, how would you define “listening”? What, to you, are the hallmarks of the truly sincere listener?

Craig: It doesn’t seem fair to try to describe listening from any perspective other than that of an engineer and 1950’s style nerd, who’s learned much the hard way.

For example, listening is beyond hearing in that, for my people, it’s an implicit request for help solving a problem, and yet, that’s often completely wrong. Sometimes the speaker just wants you to hear them, without attempting to solve anything, and without judgement.

However, in the worlds of news, nonprofit work, and in everyday transactions, there are parties who intend you harm, so you do have to judge their words. “Con man” is short for “confidence man”, which is to say that you really do need to do some real-time reality testing.

Listening also requires a certain humility, since you might be sure about something, and yet be completely wrong. The party you’re listening to might help you out by setting you straight.

I guess effective listening is about hearing what a person needs you to hear, without problem solving, just enough judgement for truth-testing, and the humility to accept when you’re wrong.

Kirk: From your perspective as a successful businessman and committed philanthropist, how important is the act of listening, especially in today’s somewhat “challenging” world?

Craig: Aside from mitigating the actions of con men and scammers, there are well-intended people who don’t listen to the people that they have good intentions about helping.

That is, say you’re listening to someone who allegedly represents some group, maybe an underserved one, you need to consider whether or not the speaker has actually listened to the group they purport to represent.

Often, nonprofits and other groups genuinely want to help an underserved population, but they feel that they know better how to help that population than the people included in that population. They might go through the motions of listening, but already had made conclusions prior to the conversation. Sometimes, in the urge to conclude what they’ve already concluded, they’ll “listen” to people who might be part of the underserved group, but who are compensated for telling the nonprofits what they want to hear.

This problem is manifest in “White Savior Syndrome”, where people of privilege want to help out, but really never listen, because they feel they know best.

Kirk: How do you believe you, yourself, have evolved as a listener? What do you do differently today than, perhaps, 10 years ago?

Craig: I try really hard to only listen to someone describing a problem, and then to avoid feeling I have to help solve the problem, unless they request that.

Even when I’m sure I’m in the right, I try to consider that I might be very much in the wrong, and, sometimes that’s definitely the case.

Kirk: What role does “ethics” play in listening?

Craig: The core of ethics, for me, is to treat people like I want to be treated.

Well, I’d like to be listened to, seriously, so I should do so with others. (I probably fail at that more often than I’d like.)

Kirk: From an ethical standpoint, what difference can ethical listening make in an organization’s …or a government’s…plans and programs?

Craig: Per #2, and White Savior Syndrome, an organization which listens ethically might actually do the job they intend to do, rather than making things worse.

Kirk: How are we (the world, that is) doing on that level? Is there a particular

organization that, to you, epitomizes the concept of ethical listening?

Craig: I can’t think of one, but I do get useful help from the books of Deborah Tannen.

Kirk: I know I, for one, will be sharing this interview with my Communication students at The University of Tampa. What advice do you have for the thousands of young men and women who will, at some point, become our business and government leaders? What should they be doing today to prepare for tomorrow?

Craig: Treat people like they want to be treated.

That means listening with humility.

That means forgetting what you think you know.

That means good listening as requisite to good customer service.

Ivar A. Fahsing (Ph.D.) is one of the world leaders in the field of investigative management. Dr. Fahsing truly holds that an improved understanding of the value of listening is fundamental to success within the law and the security sector. Dr. Fahsing is currently on a 1-year unpaid leave from his daily position as an Associate Professor and Detective Chief Superintendent at the Norwegian Police University College in Oslo. Dr. Fahsing has been hired as a subject matter expert by the International division at Centre for Human Rights – Faculty of Law, University of Oslo.

William Patrick McPhilamy III (JD) Director (Judicial Listening) GLC and a renowned lawyer who was recently appointed as Ambassador at Arbitrator Intelligence. He has been practicing law for over 20 years. He graduated from the University of Cambridge with a Master of Law degree; California Western School of Law with a Juris Doctor; and Virginia Commonwealth University with a BS. He also has a Diploma, Institute on International and Comparative Law in London, England, from the San Diego School of Law, and he has studied law at the University of Oxford.

William: Prof. Fahsing in 2009 you wrote an article on investigative interviewing, and suggested that training in the area was in development. Since that time you have written several articles on this topic. Would you tell us how developed that training is now, and how you address listening in the context of an investigative interview?

Ivar: How the state meets a crime suspect in a high-stakes situation is in my view the acid test of a true democracy. As stated a very long time ago by Sigmund Freud: “The first requisite of civilization is that of justice.” A better recognition in the global law and security sector of how something as elementary as listening might help us put into practice fundamental democratic principles, such as rule of law, equality, dignity and respect. Promoting listening in security and law may help us keep our societies safe and free. Therefore, all public servants should listen more than they talk.

I am currently on a leave from the police while working full-time with the Norwegian Centre for Human Rights at the University of Oslo. With the support of the Norwegian government and in companionship with other partners around the world, our aim is to improve human rights compliance within the chain of justice, including judges, prosecutors and the police. To this end, we teach judges, prosecutors and police detectives investigative interviewing methods that could contribute to preventing torture and errors of justice and cooperate with the UNODC (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime), UNPOL (The United Nations Police) and UN Special Rapporteur on Torture to develop global standards for police investigation. Listening skills in combination open-ended questions have the power to help us counteract social stereotypes and cognitive biases that otherwise might ruin criminal investigations, and a number of other critical and complex operations.

William: You are on the police academy faculty–is listening taught in any of the academy’s coursework? If so, could you describe it?

Ivar: The way a police officer meets and communicates with a random bystander, a victim, a witness or a suspect of a crime is, in my view, the acid test of professionalism. That is why the Norwegian Police University College favours empathy and communication skills as a critical feature all the way from recruitment of future officers and through our three-year bachelor studies in policing. The ability to actively listen and think before you speak is essential at all levels of our education. We firmly believe that this helps us to solve our most difficult tasks in a better way–no matter what the case or your level of specialization. Still, how we communicate also affects how citizens think about us. Annual citizen surveys in Norway show that police officers are amongst the professional groups that score the highest when it comes to trust amongst the population. Hence, investigative interviews in their myriad forms are contact points between the state and the public – their importance should not be underestimated.

William: I noticed 35 of your articles listed on your page of the police academy website. Do any of these describe your approach to listening in some detail?

Ivar: Yes–a number of my articles, books and book chapters do since listening is so fundamental in the scientific approach to communication in law which we call investigative interviewing. Here is a summary from a blog I wrote on the homepage of the British government in 2018: https://blogs.fcdo.gov.uk/fcoeditorial/2018/06/26/uk-interviewing-and-investigation-techniques-take-a-detour-through-norway-and-go-global/

William: What is your approach to listening?

Ivar: A better recognition in the law and security sector of how something as elementary as listening might help us put into practice fundamental democratic principles such as the rule of law, equality, dignity and respect. The opposite of an open-minded listening approach is, in my view known as coercive interrogation techniques or even worse–outright torture. Sadly, are such highly unethical and dangerous methods still in use around the globe, causing nothing but suffering, distrust and unreliable evidence. Investigative interviewing and active listening techniques is a science‐based approach which is developed as a human rights-compliant alternative to coercive interrogation methods. Listening in combination with open-ended questions will maximize the information obtained whilst minimizing the risks to the interviewee, the integrity of the investigative process and the overall criminal justice system.

William: Did any of your mentors, or teachers, emphasize or discuss the importance of listening?

Ivar: Oh–I could name several, but if I have to pick one, it must be Prof. Ray Bull from England. He is a pioneer and one of the world’s leading experts in forensic psychology investigative interviewing. I was fortunate enough to learn from him more than 20 years ago when we set out to change the way then Norwegian Police did their interviews with suspects. Prof. Bull and his colleagues have always pointed out that the interviewers ability to listen and to maintain the use of open-ended questions the most defining characteristic of an expert interviewer.

William: How do you think listening might promote peace and justice? Do situations like those of George Floyd and others in the USA point to issues with not listening?

Ivar: As stated above, I think good listening is perhaps the best indicator of a professional police officer. Listening requires and signifies both empathy and respect. At the same, it will give you information, and hence promote better judgements and decision-making. I understand that the problems which we now see unfolding in the US and elsewhere are complex, complicated and difficult. Listening alone will not solve all these problems. Still, I feel confident that officers with good communication skills run a much lower risk of having to resort to power or violence. Trust is essential. In smaller, more ethnically homogeneous countries like Norway, building trust is easier. There are, however, now shortcuts to a better relationship. Officers in should focus on building trust at the lowest level possible and multiply out from there. Officers should be on foot rather than in cars. They should talk to people, listen and get to know them. By doing more of that, you will slowly start building more trust. To be honest, I think all police services around the world should do more of this—more should also be done in my own country. Trust is something you have to create and earn, every day.

William: Most of us know about criminal investigation from what we see on television, in the movies, or in the news. How would you contrast what you do as an investigator with these characters and their behaviors? That is: How do you relate to the way detectives communicate and listen on television detective/crime shows.

Ivar: It should come as no surprise that the way detectives typically are depicted in movies, and TV productions are very far from how we train our officers. The heroes on the screen are often aggressive, stubborn and narrow-minded. This is the exact opposite of what we are looking for in a good detective. Listening is useful for a number of reasons, both inside and outside of the police station. On the other hand, it is probably not the most entertaining thing to watch on TV.

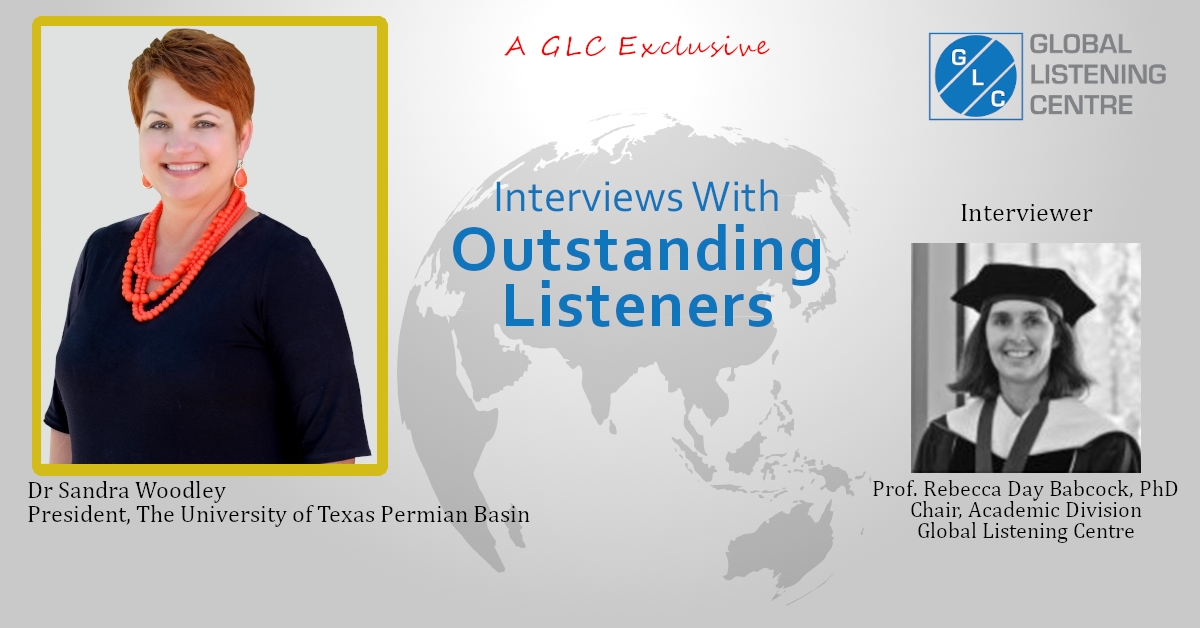

Our Executive Editor, Dr Rebecca Babcock, interviewed Dr Sandra Woodley, President, The University of Texas Permian Basin.

Rebecca: Thank you for agreeing to do this interview for the Global Listening Centre. Looking at this figure of leadership types, which type of leader do you believe yourself to be in these quadrants, and how does that leadership style affect your listening?

Sandy: When I look at the quadrants it’s a little like personality tests and management tests. You can really see yourself a little bit in every single one of the quadrants. For example, when I look at the quadrant where I have a check mark by every attribute, I think, quite honestly, I am most concentrated between the Listening Leader and the Driver. I do end up having a very strong direction and a sense of urgency around accomplishing goals. And I do think that I struggle constantly in my professional career to improve listening. It doesn’t come easily to me. I end up talking more than I listen. And I think part of my own professional development over the past 10-15 years has been, I really need to work on making sure that I really do stop and listen and legitimately try to understand all of the perspectives before making a decision. But by nature I’m a decisive person. I genuinely do care about what other people say about what’s going on. I want to make sure that I look at relationships as a way to understand the issue and to validate the different opinions. I think the only aspect on the Listening Leader that was questionable to me–I had check marks by everyone except for “may get bogged down in process.“ I don’t tend to get bogged down in process. I think process is really important. So I think that I got most of the check marks by Listening Leader and Driver. If I look at Peacekeeper, certainly I think it is true that I place a high value on relationships, and I do have a caring disposition. At the same time, I am not inclined to do the work for others instead of letting them do it. So that’s really not me. Also, I do not necessarily listen to the loudest voice. And I do not avoid difficult conversations. So, less really on the Peacekeeper. When I look at Manager, I do work really hard at keeping things running smoothly. Managing is a lot of what I do. Complying with directives– I am a rule follower. I want to make sure that we do things properly. I don’t think I generally neglect relationships. And I am not a micromanager. So that was a very long way to say I have a little bit of the attributes of all of them. I think I’m really more in between a Listening Leader and a Driver.

Rebecca: But I see you more as a change agent than keeping to the status quo.

Sandy: Most definitely. I think that’s true. And I think I’m probably midway between facilitate and top down. That’s how I would describe myself. I am sure my husband may describe me differently. And maybe other people will describe me differently. But that is my perception of myself.

Rebecca: Since you’ve been at UTPB, we have seen a lot of changes and that’s what we wanted. So it makes sense.

Sandy: Right.

Rebecca: So give me an example of your leadership style affecting your listening. Do you feel your listening was positively or negatively affected and why or why not?

Sandy: As I said before, I think generally, if I’m honest with myself, I am not as good a listener as I need to be. I am not. I think is not my strong suit. It is not my natural inclination to wait until everyone has talked for me to insert what I think about the issue, and I think that’s an area that I genuinely do try to improve. But, I am an extrovert; I have a lot of responsibilities. I think very deeply and thoughtfully about the initiatives of the university, and I have strong opinions. And so, my work professionally with myself is to make sure that I do, or at least I am cognizant, and I think I am aware, that I need to improve what is not a natural inclination to me to get more information before making decisions. And I think I have made some progress in my life at working on that. But I still need more work.

Rebecca: How can you get everyone’s opinion when there are thousands of people whose opinions are out there?

Sandy: It’s not always practical, but I do think it is important to make sure that there is a way to facilitate dissenting opinions. I consider myself a secure person and a secure leader. I am not threatened at all by someone who thinks differently than me. I am not afraid to be challenged. I genuinely do believe that the way that we make the most progress as leaders of organizations is to really tease out an honest debate about whatever issue is at hand. So when people disagree, I prefer that they disagree respectfully, but I don’t get offended if they don’t. If they’re not respectful. I think you’ve noticed. Hopefully you’ve noticed that about me.

Rebecca: [laughs]

Sandy: I don’t take it personally, I think, is really the better way to say that. And so trying to make sure that there is an opportunity for all viewpoints to come together is ideal. I do also think it is important to be decisive enough that you can make decisions and move on. I have seen leaders who are very intent on getting all of the information and listening, and listening, and listening, to the point to where you have a paralysis by analysis and you don’t make a decision. You have to be assertive enough get enough information to make the decision, but move forward in a manner that actually is timely enough to get the job done.

Rebecca: That’s why you didn’t check “get bogged down in process.”

Sandy: Because I’ve got stuff to do. I’ve gotta move.

Rebecca: It would take too long to check in with each and every person on every issue. Listening obviously is a very complex process, so what aspects do you consider when you listen?

Sandy: It also depends on the decision that is on the table, who is involved in the decision-making process, what the stakes are of the particular initiative that you are talking about, and so I think it really depends on the situation, all of the things that do come into play. When I look at power differences in age for example, I think about how earnest that I try to be in understanding our students.

Rebecca: They are a different generation.

Sandy: They are vulnerable, and they don’t have power. Their opinions matter more than almost anybody else’s around here, really, because they are who we are here to serve. I do have a very strong sense of justice, in the sense of I want to make sure that I have an opportunity to level the playing field for people or situations where they don’t have the power for themselves to speak up or the political capital to speak up. And so it’s really important to me to make sure that there’s balance in the conversation. Back to the loudest person in the room. Sometimes the loudest person in the room is right, and sometimes they’re not. And most of the decisions that a president makes is not a consensus. You want to understand all of the complexities of what you are trying to do. But there may be an overwhelming popular consensus for something that really would be detrimental to the university. I am the one that’s responsible for that. So I’m not managing by popular vote, even if I do want to understand everyone’s opinion. Does that make sense?

Rebecca: Yes.

Sandy: And so I think non-verbals are important too. I find it important in my own dealings with my executive staff, or when I’m meeting with faculty, or when I’m meeting with the STEM academy1, when there are really very emotional issues at stake, to try to look at the non-verbal cues. I have been in meetings where you have very introverted people, who are very well respected, very smart, but they will not automatically speak up when you have a lot of loud voices clanging around each other. In those instances, I try to pick up on those non-verbal cues and give a voice to someone that may not speak up on their own, but really might have something very important to say. And at the same time, I think the non-verbal cues of, when someone is getting upset, and they feel very strongly about something, well, I wanna know more about why you are so upset. What am I missing that I didn’t know? There have been times where you are in a conversation and someone is getting very upset, and you’re thinking, I don’t even understand why you’re so—but then if I can listen and draw it out, oh well, I didn’t know that piece of the story, now I understand why you are so positively impacted by the decision that we’d make here. So I do think it varies based on what’s going on and the environment is another important point. If I have a town hall meeting with hundreds of people, it’s a very difficult venue to gain knowledge and information about what the group thinks. That environment does not really lend itself to the kind of knowledge that I may need, but yet that town hall meeting may be very important for the people in that room to be able to see me and to be able to hear what I have to say. So in that sense I’m not listening at all.

Rebecca: Well, it’s two ways. They have to listen to you, too.

Sandy: They have to listen to me, and then I try to facilitate later. And I think the STEM academy is an example of that. I mean, we are going through a task force with meetings now to make sure that we can find a positive outcome for the STEM academy to continue, and trying to really listen to what the parents think and what the teachers think and what the students think and what the realities on the ground are about, what we can and cannot do going forward. It’s messy; it’s complicated. And that’s OK. It’s like the washing machine method where you agitate on something for a while, and say, OK, well, let’s see. And then a month later you go back and revisit, and you learn a little bit more and make a little more progress.

Rebecca: The next question is about active listening. How do you define active listening, what does it entail for you?

Sandy: Well the standard definition of course, is you are listening with of all your faculties, not just not with your ears. You are paying attention; you are not on your phone. You are trying to gain a deeper understanding of what someone is trying to say, I think active listening is facilitated by listening and asking good questions so that you pay attention. Don’t ask a question that they just told you that you weren’t paying attention to, because we are all guilty of that. I just answered that question! I think those things are important in active listening. I think very few people do it well. To be honest, I think very few CEOs do it well. And I am in that category. I think it is important to continue to learn about listening skills. I am very supportive of the Global Listening Centre. We all have a lot to learn. Particularly in this day and age where opinions and thoughts are so polarized. People consume their information through very biased venues. We all do.

Rebecca: Yes, yes.

Sandy: Like you said before the interview started that you didn’t believe in smartphones. Well, I do believe in smartphones. Part of the downfall is that I read through my newsfeed, and it feeds me the things that I click on that I’m interested in. So, I am not getting the complete picture. And the same is true with someone who has a different set of views. So trying to find a way to cut through what is fact and what is opinion, which is difficult these days, and listening to each other, is important.

Rebecca: My students say they pick up their news from international sources. Because they are less biased than US news services. They use the BBC. Supposedly it’s less biased.

Sandy: There’s bias in all of it. And I think that it’s important, even as uncomfortable as it is, to read something that you disagree with, that you know is biased in the other direction, so that it helps you to triangulate. And try to get to facts as opposed to alternative facts.

Rebecca: And why someone would feel that way, because everyone has good will, we hope.

Sandy: And some don’t. Let’s just face it. People have agendas. There are instances where you’re spinning information to the point where it actually is untrue. There are examples of that on all sides of any topic that you can listen to or that you can observe. As a CEO of an institution, I feel very strongly that it’s important to make sure, number one, to the extent that we can, that everyone has the same set of facts. If it’s not a fact, it doesn’t belong in the list of facts. So let’s try to get what’s verifiable on any topic or issue that we’re talking about, and then let’s categorize the rest of the information as questions, or opinions, or feelings or concerns. That’s when I think you can get to a conversation where people can really listen to each other, and you don’t have to debate what can already be verified in another way.

Rebecca: Can you give me an example of when you listened actively, and how you deconstructed a surface narrative?

Sandy: So let’s use the STEM academy because I think I’ve done that well and I’ve done it not well. I think I have room to improve, and I think I’ve learned from that. When we went down the pathway of trying to find a long-term option for STEM, I really didn’t estimate properly the opinions of the STEM family.

Rebecca: They love their school.