Listening on Both Sides of the Abortion Issue: A Major Challenge to Advocates

Katherine van Wormer

Professor Emerita of Social Work

University of Northern Iowa

Co-Author of The Maid Narratives

Listening often poses challenges when we disagree with others who have opposing views and different experiences, but the more different we are or more we disagree, the more important our listening becomes. Over the last year, one such issue has become salient for women in the U.S.

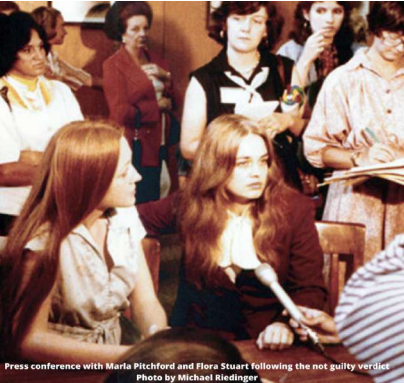

The issue of abortion has a special meaning for me because of my personal witness and involvement behind the scenes of a harrowing 1978 trial. A young woman (Marla Pitchford) who had almost died after self-inducing an abortion with a knitting needle was indicted for manslaughter and performing an illegal abortion. The trial took place in Bowling Green, Kentucky. My sister, her primary defense attorney and confidante, won her acquittal after months of meticulous research and preparation. Recently, with the overturning of women’s right to an abortion in Roe v. Wade, my interest in the case and in the abortion was revived.

An Aside on the Role of Listening in the Marla Pitchford Case

Although the focus of this article is not on this trial (known as the Marla Pitchford case), from the standpoint of today and my work through the Global Listening Centre, I can briefly consider the crucial role that listening played at every step of the legal defense. First, a survey was conducted of townspeople in Bowling Green who had read of the case. Surveyors attended closely to what these people thought on various aspects of the young woman’s situation. Meanwhile, the lawyers worked closely with the defendant and consulted with psychologists to develop a full understanding of her state of mind when she plunged the knitting needle into herself. To this end, my sister and Marla had many woman-to-woman conversations. This personal connectedness enabled the defense to effectively convey to the court in dramatic opening and closing statements the intensity of Marla’s feelings (when her boyfriend had abandoned her). In her opening statement to the jury, my sister asked the jurors to put themselves in this woman’s place and imagine what their feelings would be under the same circumstances. Because the same listening skills had been applied to potential witnesses for the defense, the lawyers knew who to put on the witness stand and the likelihood of their persuading the jury with their arguments. So, as I look back to this example of courtroom justice today, I can see that a major factor in the successful legal defense is through careful and purposeful listening.

Active, Empathic Listening

Just as active listening is a crucial element in the practice of law, so it is an invaluable attribute in other contexts as well. As described in the classic teachings of psychologist Carl Rogers, active listening goes beyond merely paying attention to a speaker; it involves much more than passively absorbing the words that are spoken, as for example, in a teacher-learner situation. Active, nonjudgmental listening to Rogers was a process that he found to be a highly effective form of communication— in therapy, in conflict resolution, and in ordinary conversation. His videos, produced from the 1950s through the 1970s, provided trainings for counselors in techniques designed to help the therapist grasp the facts and feelings expressed by the client. Through skilled paraphrasing, the therapist as listener, can pick up on positives and reinforce them as a way of eliciting hope. These teachings which Rogers demonstrated in filmed therapy sessions with his clients, he regarded as applicable to his everyday relationships.

Genuineness, unconditional positive regard, and empathic understanding—these are the three components of a therapeutic relationship as singled out by Rogers. These qualities, which are basic to effective listening, are inextricably linked. Empathy, for example, promotes one’s positive regard for the other person, but these two traits if not perceived as genuine would be of little or no value. These concepts, which are the foundation for active listening are postulated in the theoretical framework of Rogers’ person-centered theory.

Abortion as a Volatile Issue

During the early years after Roe v. Wade (passed in 1973) was put into law, most Americans, apart from strict Catholics, seemed to accept the reality of legalized abortion in the same way they did advances in civil rights, gay marriage, and so on. Such was the social climate in 1978 when Marla Pitchford’s prosecution became the first case in the U.S. involving the prosecution of a woman for a self-induced abortion. But changes in attitude were slowly evolving along with a surgency in strength of evangelical Christians and a transition in focus, and the arrests of women for suspected damage done to their fetuses, such as through illegal drug use, became increasingly common. Meanwhile, remarkable developments in medicine made fetuses viable at an earlier stage than before; this ability to save infants at ever earlier stages of development gave resonance to the movement to further restrict abortions. Newly available graphic images of fetuses at various stages of development could now be used to arouse strong feelings and beliefs concerning the beginning of life. As a result, many former moderates and pro-choice Republicans aligned with the religious right to campaign in favor of laws banning abortion. This fervor was matched by strong passions in feminists who were ready to fight for women’s reproductive freedom. News reports of protest rallies over the issue revealed that there was much shouting and name calling of adversaries on both sides.

Lessons Applied to the U.S. Abortion Conflict

Now we can take the emotionally fraught and divisive issue of abortion as a case in point to see the extent to which active listening skills might apply, might, in fact, defuse the tension.

Emotions are our worst enemy. This is what Carl Rogers said. He was referring to the listener’s own emotions, but emotions in the other person too can be damaging. Out-ofcontrol emotions are contagious and tend to escalate in bouts of disagreement. Self-awareness, as Roger suggested, is key to understanding one’s emotional responses and

The emotional impact of this abortion trial shows on the faces

of the witnesses as the lawyer and her client speak to the press

gaining control over them. Listening to oneself, he viewed as a prerequisite to listening to others.

Empathy provides the ability to understand another person’s experience in the world, as if you were that person. The gift of empathic listening is evident in body language, voice tones, and the words that are used.

Applied to the cultural wars over abortion, (or immigration, police violence, or any other contentious topics) one would want to avoid a heated argument and just enjoy an amiable conversation. It’s interesting to know where a friend or family member stands. In a trusted relationship there can be disagreement without animosity. Should the discussion be getting out of hand, it takes only one person to defuse the situation. Humor and empathy go a long way to relieve the tension. Just as violence breeds violence so empathy begets empathy. As the Bible teaches us: “A soft answer turneth away wrath: but grievous words stir up anger” (Proverbs 15:1). Both Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King (who encountered a great deal of personal hostility) were inspired by a related biblical theme—that a single light can dispel darkness.

As a case example, we consider the perspective of an individual who strongly believes it is a woman’s right to choose whether to end an unwanted pregnancy. This person, let’s say, is speaking to a friend who is passionately pro-life, and seemingly gearing up for an argument. The active listener in this situation might respond by acknowledging the friend’s concern for infants and children and aspects of abortion that are disturbing to himself or herself. Appreciation of the person’s strong religious faith (if it is a factor) might be expressed. Both might agree on the difficulty of a situation in which the possibility of giving life to a baby is not going to be realized. In the ideal situation, the pro-life person will respond in kind with recognition that his or her friend has a sincere concern about the woman’s difficult situation in having the child. In any case, the focus would be on finding common ground. The discussion could end, for example, with both agreeing that if greater financial support was given to a family after the birth of a child, there would be fewer women having abortions.

In the worst-case scenario, the pro-life individual might enter in a tirade against women who have had an abortion or their supporters, viewing abortion in terms of murder. In dealing with such emotionalism, the listener would do well to consider such hostility could be stemming from another source, and with that understanding in mind, choose not to pursue the abortion issue any further. Hopefully, the friend might benefit by getting help in other areas of his or her life that might be closer to the source of the anger.

In the same way that the pro-choice person can seek reconciliation through active listening, so the staunchly pro-life person can recognize the feminist’s concern for the health and welfare of women and turn the focus to their mutual concern for babies after they are brought into the world. Through momentarily putting oneself in the place of the advocate for women’s rights, the active listener of an anti-abortion persuasion can show a respect for the other’s point of view. Phrases such as “I see where you are coming from” if said in a calm tone of voice can be helpful.

Keep in mind if this approach of empathic listening works for differences over attitudes about abortion, it should work in other areas of highly charged discourse as well, many that arise unexpectantly in conversation. Difficult topics such as immigration, political ties, and gender identity issues have a way of cropping up when the sentiments concerning them are strong or following a report on the news. The three basic tenets of Rogers’ theory— genuineness, unconditional positive regard, and empathic understanding—will go a long way toward preventing conflict and enriching a relationship.

References

Rogers, C.R. (1980). A way of being. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company Rogers, C. R., & Farson, R. E. (1957). Active listening. Chicago, IL: Industrial Relations Center of the University of Chicago.

Van Wormer, K.S. (2022, June 20). What a 1978 trial could tell us about future abortion cases. Washington Post. Retrieved from https:// www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/2022/06/20/marla-pitchford-case1978-abortion/